When the Iraqi soldiers plunder Ranjit’s house, they are at first struck by its opulence. When Ranjit’s in his car driving through the city that has been destroyed by the Iraqi army, we see, in a fleeting shot, Kuwaitis being harassed in the streets - these scenes are not particularly essential to this story, but it was to that moment in time where Airlift derives inspiration from. When the Iraqi army attacks Kuwait in the night, we see a man, presumably a Kuwaiti, come out to the balcony of his house, dressed in pajamas, devastated by what’s being done to his country. The film is not just about Indians in Kuwait, but also Kuwaitis in Kuwait. Kumar’s Ranjit is indeed a hero, but the film doesn’t necessarily see him as one, merely as someone who was able to find moral courage through a deeply personal loss.Īirlift also often sweats the small stuff, and does it remarkably well. And it’s heartening that Raja Menon, Airlift’s director, believes it’s important that Ranjit first earns our trust - through small moments like these - before becoming a messiah for others.įor a film like Airlift, based on the lives of a few men who felt doing the right thing was vital, it is important that the film itself is humane, finding hope and humour in squalor. Which is why Ranjit’s transformation, one that’s absolutely central to this film, doesn’t ring false. It’s an important scene because mainstream Hindi films are not known for their moral fiber, definitely not in a way that’s this unassuming and simple. Airlift doesn’t demarcate between human lives. When Ranjit goes to strike a deal with his the Major of Iraqi Republican Army, he agrees to pay for the safety of not three people (his family) but five (his driver’s wife and her daughter). And even after this scene, Ranjit, and, consequently, this film, doesn’t discard her, or her daughter he brings them to his office, now a makeshift shelter for many Indians in Kuwait, and assures them of their safety.

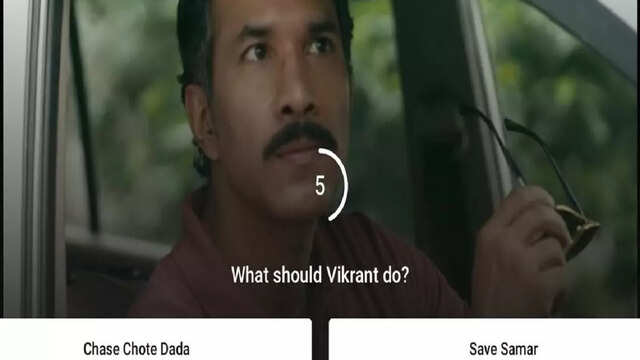

#Airlift hindi movie last scene for whatsaop status driver

As he stands outside the house of his driver to inform his wife about her husband’s death, he can barely speak a word. Because it knows what’s far more important in a story based on a real-life event: faceless, nameless ordinary people totaling to more than a lakh and a half, who are stranded between the cowardice and indifference of their adoptive and native countries.īut before Ranjit takes up the cause of thousands of strangers, he starts with his own people first.

Most commercial films would have used this plot point to launch into a narrative centered on the larger-than-life persona of its hero. He sees the sorrows and anxieties of his own countrymen, especially ones less privileged than him, and begins doing his bit to set their lives right (even at the cost of complicating his own life). Ranjit can’t care less about India and Indians, but a few days later, when his driver gets shot, on the first morning of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, something stirs in him. The film lets the driver have this moment. Ranjit remains comically dismissive but Amita tells him to keep quiet.

Ranjit, who considers himself more Kuwaiti than Indian, scoffs at the choice of song and tells his chauffeur to play a different track, presumably something non-Hindi.Ī few hours later, in the same night, while Ranjit’s in the car with his wife, Amita (Nimrat Kaur), the driver tells them that he’s planning to visit India with his family, which includes his daughter who has never seen the country. In one of the earlier scenes in the film, set in 1990’s Kuwait, Ranjit Katyal (Kumar), an influential businessman, gets inside his car, and his driver switches on the stereo that plays a Hindi film song, Ek Do Teen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)